Joseph Beuys +

By Giorgio Conti

2004. Twenty years have passed since the Defense of Nature operation promoted by Joseph Beuys in Abruzzo, an italian region.

Even though this philosophical-artistic-socio-cultural-scientific action was conceived in

The reflections that follow mark out the role that Italy has played in redefining the poetry and philosophy of Beuys and especially his "expanded" concept of art: art = man = creativity = science. The reflections were written down in 1997 in order to make it clear that, if it is true that Andy Warhol has created a global image of 20th Century Western society, Beuys donated a strategic vision of criticality and potentiality of the 21st.

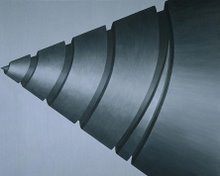

Within the vision of Nature and the world of Beuysian thinking, the central theme is energy.

A natural energy, stated in the cosmic/alchemic sense: "We plant trees and the trees then plant us". A global defence of natural cycles (the temporal dimension) and especially that of biodiversity, intended as protection of local and global ecosystems (the spatial dimension).

A vital energy that in Social sculpture becomes an anthem to human creativity: a concept broadened of the artistic work.

A primary art, anthropological, which, even today, is able to dialogue with research into a new developmental model pertaining to the strategies of integrated environmental, economic, socio-cultural and ethical sustainability.

His proposal of a Third path represents a welding between criticality-potentiality extra humans (the privileged relationship man-Nature) and of criticality-potentiality among humans (the overcoming of conflicts both at a local and global level).

Even the materials used in his works and/or performances are the fruit of energetic processes or contain energetic elements: sulphur, bee's wax, fat, felt, copper, etc., right on till we get to blood: the metaphor for antonomasia of Life.

The concept of Freedom, furthermore, shows a sense of the value of original energy throughout the works and thoughts of Beuys, in that they are able to rejuvenate and stimulate - through creativity - the resources of natural organisms (ecosystems), and of the single organism (the human being), as well as the social organisms (humanity).

by Joan Rothfuss, Walker Art Center curator

Joseph Beuys' fascination with plants, animals, and the natural sciences developed early and remained strong throughout his life. As a child, he collected local plants and insects and catalogued them in notebooks. He also set up an extensive laboratory in his parents' apartment and conducted experiments in chemistry and physics. His first career plans were to study medicine and become a pediatrician. Though eventually he enrolled in art school instead, he retained his personal interest in the natural world, becoming especially well-versed in the properties of herbs and their use in natural remedies.

In his early interactions with nature he had used the principles of the traditional scientific method--observation, experimentation, recording of data. In his artwork, however, he referenced nature poetically, as metaphor or symbol. For example, the many images of waterfalls, rivers, geysers, glaciers, and mountains that appear in his drawings and prints are not traditional landscapes, but rather references to the primeval sculpting of the earth's surface by natural forces. Another recurring metaphor is found in his many images of a human-figure-as-plant whose head sprouts "roots" that extend into the clouds. This fantastic image was Beuys' assertion that while man is an earthly being, he is nourished through the spirit.

The bridge between the earthly and spiritual realms is represented in Beuys' work more often by animals, which he thought of as "figures that pass freely from one level of existence to another." In many cultures animals are guardian spirits for shamans, companions on their celestial journeys. Beuys often used animals in his actions, bringing them along, so to speak, on his own journeys. He carried a dead hare in several early performances, shared the stage with a spectral white horse in the action Titus/Iphigenia (1969), and most famously, spent a week in a gallery space with a coyote in I Like America and America Likes Me (1974), an action described as a "dialogue" with the animal. All of these performances suggest the shaman's special affinity with animals: he can understand their language, share their particular abilities, even transform himself into one of them.

Beuys identified personally with several animals, most notably the hare. He always carried a rabbit's foot or tuft of rabbit fur as a talisman, and jokingly cited the pointed shape of his ears as proof of his close relationship to the creature. He also had an affinity for the stag, an animal with deep ties to Germanic legend and northern myth; he sometimes referred to himself as "stagleader." And in the multiple A Party for Animals (1969), he simply declared himself to be an animal by including his own name--along with those of the elk, wolf, beaver, horse, stork, and many others--on the list of the party's "active members." For Beuys, maintaining a close relationship with animals was crucial for him so that he could learn from what he believed was their superior intelligence (intuition).

Strengthening the link between art and science, or intuition and logic, was a key concept for Beuys and the basis for his identification with Leonardo da Vinci. On view here are his two notebooks of prints inspired by da Vinci's Codices Madrid (14911505), a pair of sketchbooks by the Renaissance master that were discovered in 1965. Beuys saw his images as contemporary counterparts to da Vinci's sketches--his own attempt, at the end of the 20th century, to make visible the underlying connections among technology, the natural world, and the arts.

-Joan Rothfuss,

Walker Art Center curator

![]()

ENERGY PLAN FOR THE WESTERN MAN

Joseph Beuys visited

Feldman and Stoller organized a 10-day, three-city circuit with stops in

The debates, discussions, and press conferences formed the artwork, but for those who were unable to attend the talks Beuys produced some 16 multiples, most of which are on view in this exhibition. Many of them have an anecdote attached. One features an image of a rabbit that Beuys noticed on a sugar packet while dining at Nye's Polonaise Room in

The suite of six prints entitled Minneapolis Fragments (1977) began when Beuys drew on zinc printing plates instead of a blackboard during his

Beuys named the lecture tour "Energy Plan for the Western Man" and saw it as a chance to reinvigorate an enervated Western culture that was on the brink (at least in the

Every man is an artist.

Joseph Beuys

I think the tree is an element of regeneration which in itself is a concept of time.

Joseph Beuys

I wish to go more and more outside to be among the problems of nature and problems of human beings in their working places.

Joseph Beuys

I wished to go completely outside and to make a symbolic start for my enterprise of regenerating the life of humankind within the body of society and to prepare a positive future in this context.

Joseph Beuys

In places like universities, where everyone talks too rationally, it is necessary for a kind of enchanter to appear.

Joseph Beuys

Let's talk of a system that transforms all the social organisms into a work of art, in which the entire process of work is included... something in which the principle of production and consumption takes on a form of quality. It's a Gigantic project.

Joseph Beuys

No comments:

Post a Comment