Issue 5 Winter 2001/02 ![]()

What's in a Name

A few years ago, an odd machine whirred in a back room at

Signature Piece, as the machine was called, was a deft bit of engineering, but even more clever was its premise. That unruly stack of paper represented what should have been the artist's most valuable possession: the proof of his authorship, his signature. But the pile of scraps undercut more than the monetary value of a signature. By giving a machine the power to sign his name, Hawkinson destroyed the usual deference we give to the signature, our most common means to legally identify ourselves. And in doing so, he pointed at a long-running confusion over how identity is presented and assured, and how a signature works in that kind of transaction.

For centuries, identity was a fairly simple process, closer to God's Burning Bush tautology—"I am that I am." You were so and so, who had this seal and this family and these church birth records. Signatures helped—they've been around since Roman times, presumably as substitutions for seals—as did hereditary last names, which were a French and English invention around 1000 A.D. As the Renaissance brought economic and cultural progress to

Until the end of the 19th century, notes Alain Corbin, "a clever person could change identities at will."1A new town, a dead person's birth certificate, and maybe a strong resemblance to someone, and poof, you were him. Modern bureaucracies, new technologies, and the application of scientific methods to social problems put an end to this free-for-all. Bertillon's system of cranial measurements started the move to definite ID; that was superseded by Scotland Yard's fingerprinting system, which in turn is being replaced by ever-more-specific ID technologies such as iris scanning. Through all of these changes, though, the signature has remained the accepted proof of who you are.

The search for verifiable identity intersected another of the 19th century's revolutions—electricity. Soon after the domestication of this natural force, people began thinking about how the phenomenon could be used to transmit information. By the late 1830s, British inventors and the American painter Samuel Morse had created the telegraph, and within 20 years thousands of miles of wire connected all major cities. But some were not satisfied with telegraphy. For one thing, telegrams could be faked. And dots and dashes seemed as cold and impersonal as ones and zeroes do now—they bore no trace of their creator, and thus had nothing of the real essence of their creator. So began the endless quest for more personal electric (or electronic) communications. Dots and dashes begat typed letters, and then the telegraph begat the telephone; today, ASCII-text e-mail has been largely replaced by HTML- and graphics-equipped systems such as Microsoft Outlook.

Enter the teleautograph, the 1888 creation of Elisha Gray, who had famously lost the race to patent the telephone by a few hours. It's not clear exactly why Gray thought transmitted writing would be better than transmitted words. But it didn't take much for a 19th-century inventor to start inventing. Once he got it working, his teleautograph wowed the crowds at the 1893 World's Columbian Exhibition. Here's how it worked: The transmitting person moved a writing stylus across a metal plate; its movement was measured by potentiometers. The varying levels of electricity put out by those components were transmitted by wire, just like a telegraph; the receiving instrument translated those levels into the motion of a pen-holding armature. Handwriting and signatures were finally moving through the wires.

The teleautograph never worked well over long distances, and within a couple of decades the telephone and speedy mail system had a firm hold on personal communication. But the dream of a machine that could "prove" a writer's identity reappeared after World War II with the Autopen, made for people whose signatures were in great demand.

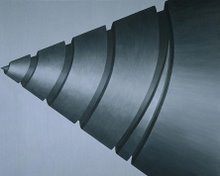

An Autopen looks like a cross between a school desk and a pantograph—an arm jutting out of a 1960s-looking enclosure grips a felt-tip pen. Inside the machine is a model of a signature; the penned arm extends out onto the desk and accurately re-creates the signature "matrix" inside, hundreds or thousands of times a day. Early users were presidents and CEOs, who could have spent weeks signing their names, barely making a dent in the demands of the important identity. (A more recent application is direct-mail marketing, which benefits from a "personal" touch.)

The Autopen was a lifesaver for important men. But the Autopen undid some of the progress that had been made in identification. Your signature, with its practiced flourish, is as close to you that writing can get. "I am that I am," your signature wants to say. And that closeness-to-you is what convinces governments and banks and landlords that you are who you claim to be. But how can that certainty exist along with a machine that can sign and sign and sign, with no care as to who has told the machine to sign? (It can't, as evidenced by a series of unauthorized, autopenned Donald Rumsfeld signatures that appeared on official documents in early 2001.2)

To say nothing of value. After the Autopen was adopted by US presidents (LBJ was a big user, as was Nixon and everyone since) it found new markets among celebrities. It really is hard to sign your name for hours and hours, but maybe not so hard as disappointing one's fans. So by the late 1960s many famous people had their own Autopens churning out signatures for the people. And while Autopen signatures from presidents and business leaders had been accepted at more or less face value, they did not have to deal with the invisible hand of the collectibles market. An Autopenned document may be good enough for the Department of Defense, but don't try to convince a collector that a machine carries the emotional—and thus, in the irrational economics of nostalgia, financial—weight of a real autograph.

A recent eBay search turned up just two Autopenned items among the 60,000-plus autographed 8x10s, books, and other baubles up for sale. And of that multitude of signatures up for bid, hundreds of their sellers went out of their way to point out that they weren't Autopenned. If we accept the opinion of the collectibles market—and as odd as that market is, there seems to be no reason not to—then eBay has become the ultimate measure of desire, value, and authenticity. And that measure says that more than a century of effort to create a mechanical stand-in for the human hand, for the written personality, has come to naught.

1 — Alain Corbin, "Backstage," in Michelle Perrot, ed., A History of Private Life, Vol. IV (Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 1990), p. 469.

2 — "Clinton-Cohen Holdovers Push Liberal Agenda at DoD," CMR Notes (May-June 2001), at

David E. Brown is a writer and editor in

No comments:

Post a Comment