|

Installation view at |

|

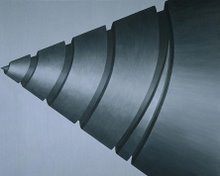

Installation views at Kitakyushu Museum, Japan, 1999. Anodized aluminum with yellow, blue, and aluminum color, 8 x 24 x 2.5 in. |

|

Installation at |

|

Installation at |

Pure space may seem very different from the actual space in which we live, but this purity stimulates our imagination. Purity means more than mere simplification. And we are made to leap into this pure space, carrying our load of complexity, moving beyond the real world with the freedom of the imagination. We do not see a world which is breaking down, a world going to ruin, a world full of amorphous human passion, or a world of simple beauty. Rather we see a world which appears beyond human perceptions, beyond settled and familiar meanings, a world which horrifies and thrills our spirit. We experience simultaneous terror and ecstasy transcending reality.2

|

|

Human existence under the predominance of space is tragic. Greek tragedy and philosophy knew about this. They knew that the Olympic gods were gods of space, one beside the other, one struggling with the other. Even Zeus was only the first of many equals, and hence subject, together with man and other gods, to the tragic law of genesis and decay. Greek tragedy, philosophy, and art were wrestling with the tragic law of our spatial existence. They were seeking for an immovable being beyond the circle of genesis and decay, greatness and self-destruction, something beyond tragedy.3

|

Somehow Tillich's concept of spatial dominance seems too overtly Western in its interpretation, too laden with the cultural weight of the past, and therefore exempt from the possibility that space exists as a reversal of form in relation to time. As a visual antidote to Tillich's theology, Kuwayama offers a reversal of form through the abstraction of the measured interval, a rhythmic punctuation that lightens the effect of the physical space. The premise of spatial dominance is suddenly transformed into a recession of form, thereby permitting a meditative pure space to evolve into the viewer's consciousness as an intentional act. We see it, for example, in the artist's recent anodized aluminum panels (what he calls channels in which two channels, measuring 19 centimeters are jointed and alternate according to two chosen colors. We see it again in the Kozo paper works in which three layers of paper are laminated through the artist's wax-pressing technique. Using modular elements in a repeatable format, Kuwayama places a single horizontal pencil line in each of six units, alternating three times between blue and red.

Installation view at |

|

|

Robert C. Morgan is a critic and artist whose books include Between Modernism and Conceptual Art.

Notes

1. The distinction between aesthetic and linguistic formalism is analyzed and discussed in my essay Formalism as a Transgressive Device in Arts, December 1989.

2. Koji Taki, Tadaaki Kuwayama's New Project in Tadaaki Kuwayama Project '96, co-published in conjunction with the two exhibitions at the Kawamura Memorial Museum of Art (June 1 - July 21, 1996) and the Chiba City Museum of Art (June 15 - August 18, 1996), p. 54.

3. Paul Tillich, Theology of Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1964), p. 33.

4. Nobuyuki Hiromoto, Objective Space: Looking Forward to Project '96, in Tadaaki Kuwayama Project '96, op. cit., p. 61.